(Note: This is an excerpt from Digital Check’s guest article on the IBT Apps blog. To read the full article, click here.)

Not too long ago, the author of a financial blog for Millennials asked if we could explain to her readers the purpose of the strange printing at the bottom of a check. Bankers will quickly realize that our blogger friend was talking about the MICR line, the magnetic printing that contains the account number and the bank routing number, probably the most important information on the check besides the amount. But most twentysomethings, and even many bankers, don’t know exactly how that magnetic printing is read, or the reason for its odd appearance (hint: the two are related).

The MICR line is so important that a scanner actually uses two completely separate reading methods to double-check each other. First, a metallic sensor about the size of a nickel, aptly named the MICR head, measures the magnetic signal; then the scanned image of the check is read optically and compared against the magnetic read.

The MICR line is so important that a scanner actually uses two completely separate reading methods to double-check each other. First, a metallic sensor about the size of a nickel, aptly named the MICR head, measures the magnetic signal; then the scanned image of the check is read optically and compared against the magnetic read.

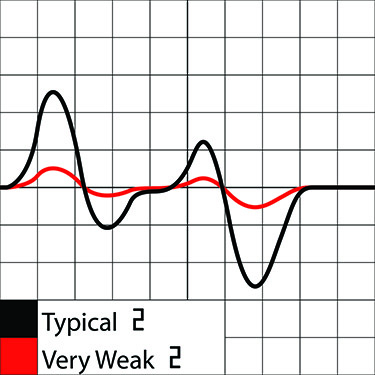

If a regular camera takes pictures in 2D, you can think of a MICR head as a 1D reader that takes a linear snapshot of the check’s magnetism, similar to how a cassette player works. As illustrated below, the amount of ink in a vertical line at any given point will give off a stronger or weaker magnetic signal, and measuring that in combination with the change over time yields a wave pattern that corresponds to a number.

Why was MICR chosen?

If you think that sounds like a lot of trouble to read fewer than 20 numbers, you’ve got a point. These days, it’s easy to just point your smartphone’s camera at something, whether it’s text or a barcode, and have it instantly tell you what it is. Optical character recognition, or OCR – the official term for having a computer “read” the text in a scanned image – is nearly instant, and more accurate than ever. Why go through all the extra effort with magnets?

The reason is because it wasn’t always that easy. When electronic check clearing began in 2004, state-of-the-art OCR had about an 80 percent read rate. Even though that figure was steadily improving, and everyone could see its potential, the hard truth was that the technology just wasn’t there yet.