If you didn’t know the reason for it, perhaps it would seem odd that Digital Check decided on Southern California as the location of its primary manufacturing facility. Given that it’s more than 2,000 miles away from our company headquarters near Chicago, one could be forgiven for thinking that we deliberately chose to make things more difficult for ourselves. But in fact, the real reason is that it was less difficult to do it that way, because the California part of Digital Check and the Chicago part of Digital Check started out as two separate companies, and it was simpler to keep each one where it was.

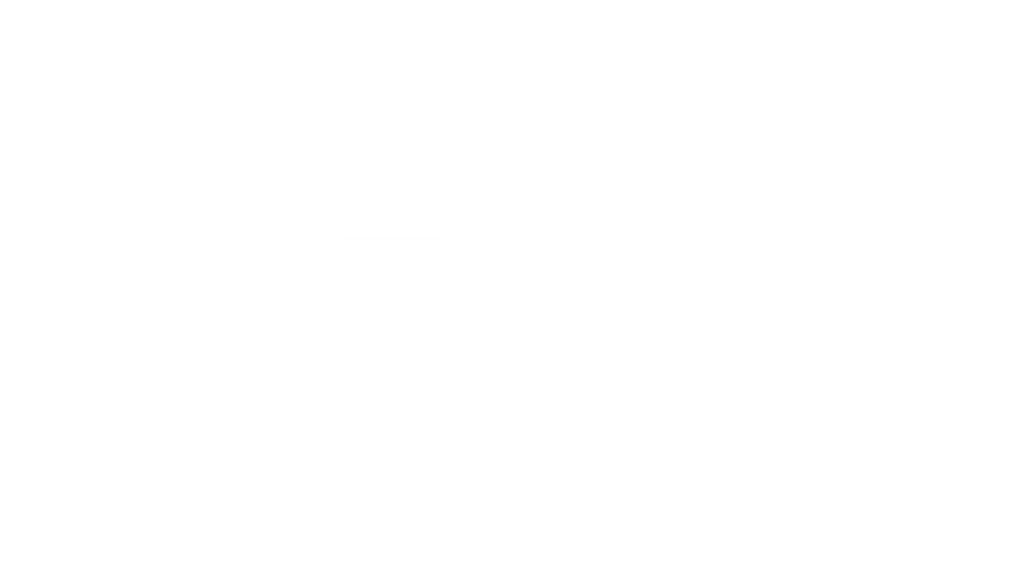

The origins of the California operation go all the way back to 1969, when a company called Optical Systems Technology (OST) was formed as a spinoff of Wollensak Optical. Those of you old enough to remember having reel-film projectors in your classrooms may be unwittingly familiar with Wollensak, as reel-to-reel school AV equipment was one of their specialties.

The centerpiece of Optical Systems Technology’s business was a new type of projector based on a stepper motor, which is a motor that turns in fixed increments rather than spinning freely. OST’s stepper motor was unique in the projection world because it could speed up, slow down, or stop instantaneously – or even reverse directions – and it did so at a maximum rate of 5,000 rpm, far faster than any other projector at the time. It’s claimed that the circuit board OST built to control the motors in an actual projector was the first-ever example of an electronically controlled film movement device.

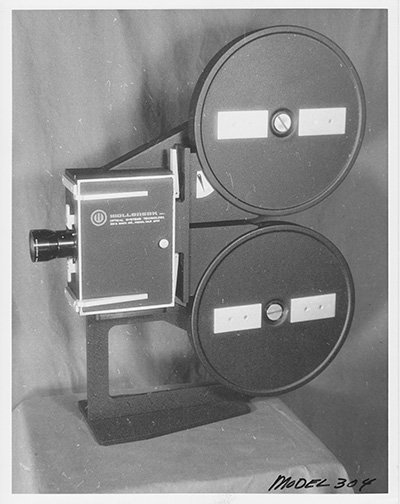

By 1971, OST had developed its new projector into a key component of a film-based flight simulator system. (How did a flight simulator that used film even work? That’s another whole story in itself; you can read more about it here.) The company won its first major contract with the Air Force to build the film transport for an F-4 Phantom flight simulator … and then it promptly went bankrupt. Nonetheless, OST was immediately reconstituted under the name Electro Optical Mechanisms, or EOM, and quickly went on to invent several of the most interesting products in our company’s history.

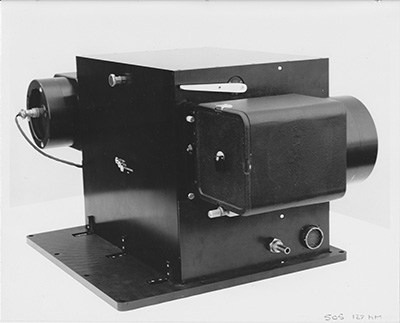

The years 1972-73 witnessed the development of EOM’s main money-maker, a line of microfilm cameras – as well as some splashy “headline” projects that were at the bleeding edge of what analog technology could do with a little digital assistance.

The EOM microfilm cameras, of which there were numerous models, mostly worked on the same principle: Some data or a copy of a document would be flashed on a monochrome screen; the camera would snap a picture of it; and then both screen and film would be advanced to the next frame to repeat the process. The precision of the electronically controlled stepper motors made it possible to synchronize that process at a much faster speed than was possible with any manual or analog process, making it ideal for the mass conversion of large collections of data. EOM enjoyed a fair amount of success in the microfilm creation business, but just as importantly, these cameras helped build a reputation for precision optics that would prove important when some high-profile clients came calling.

Meanwhile, the projector side of EOM’s business had continued to thrive, with the F4-type technology being taken up by customers like NASA (Skylab), Boeing, Union Pacific Railroad, and even shipping lines and coal mining companies to simulate the experience of operating their equipment. They also found a niche in Hollywood, where they worked so well at speeding through large reels of film that the major movie studios bought troves of them for editing all their dozens of takes and hundreds of scenes into finished motion pictures. The projectors’ powerful motors also made them among the only machines capable of accommodating an entire feature-length movie on a single reel, and so some Los Angeles-area theaters tested them in a pilot program to replace the existing projectors that used several smaller reels that had to be switched by a projectionist. That project came to a dubious end, however – read the full article for more.

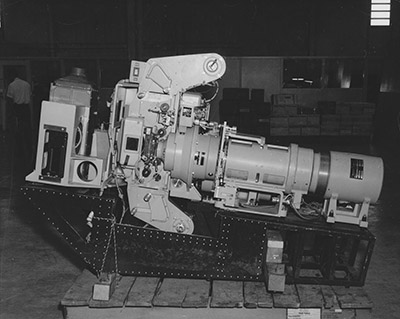

But perhaps the highest-profile project of all for EOM arose when NASA came calling, seeking a new type of ultra-high precision camera that had never been built before. This would be a large-format camera to handle film with frames more than 5 inches wide and moving no more than four ten-thousandths of an inch (0.0004”) between exposures. The camera, eventually named the Model 505, was used to translate the images beamed back by the Mariner and Viking space probes from their original format as data on magnetic reels, into visible finished photos. (More details about that process can be found here.) When you look at old photos from the earliest Mars missions, it’s almost certain that those photos were converted using an EOM Model 505 camera – perhaps the single most prominent piece of our company’s history that’s still visible even today.

One other notable project from this era was the wide-format “Metro-Set” phototypesetter that EOM developed in 1973. Phototypesetters were among the earliest machines that used a photographic process to transfer mockups of pages onto printing plates that a press would use for mass production. This was a major advance that replaced standard typesetting or linotype machines, in which rows of type had to be physically arranged (in reverse) on a mold.

EOM wasn’t the first company to make a phototypesetter, but what set its machine apart from the rest was that it could capture the full width of a newspaper broadsheet at once, and that its precision motors also allowed it to do that without any overlap. This eliminated the “seams” that plagued many early phototypesetters and made EOM very popular in the print industry for a time. (Read more here.)

Given the complexity of these different products, it’s almost incredible to think that all of this happened within just a few years! Despite the initial rough start, the beginning of the 1970s was a banner era in the early days of our company. We had pushed the limits of analog technology about as far as they would go – but soon, the digital revolution would force our company, and just about every other one like it, to reinvent itself. We’ll go further into that story in a future issue.