Last weekend, my stepson was out shooting some scenes with his high school film club. Around lunchtime, we had the following exchange of text messages:

Him: “Hi, we’re up the street at Which Wich. Can you use something called Venmo and send my friend Justin $8.50 for lunch.”

Me: “I don’t have Venmo, can I just send it to him on PayPal?”

Him: “He says you have to download Venmo.”

Me: “I don’t want to download an app and set up a new account just to pay for lunch.”

Him: “Can you use PayPal to send money to someone on Venmo?”

Me: “They’re owned by the same company, you should be able to. I’ll try that.”

Him: (long pause) … “No, that doesn’t work either.”

Me: “Can I just send the money to the sandwich place?”

Him: “No, they’re not set up for that.”

Me: “Hmm. Does your friend have Zelle?”

(long pause)

Him: “What’s Zelle?”

Me: “Never mind. Tell him I’ll just give him cash.”

That conversation largely summarizes the state of mobile payments in 2018. While the rate of growth and the number of new ways to pay are both astonishing, getting everyone on the same page is still a problem. Show any of that dialogue to a person from 1996, and he wouldn’t have the slightest idea what you were talking about – but the one thing he’d have in common with you is that cash would be the only way he could be 100 percent guaranteed of successfully giving you money.

With literally hundreds of new ways to pay for things taking shape, how could it be that cash (and to a lesser extent, the check) is still the lowest common denominator? Actually, it’s probably because there are hundreds of new ways to pay for things. With cash, you don’t have to sign up for the same service as your friend; there’s only one kind, and adoption is 100%. With mobile payments, not so much.

Like “Herd Immunity,” Only In Reverse

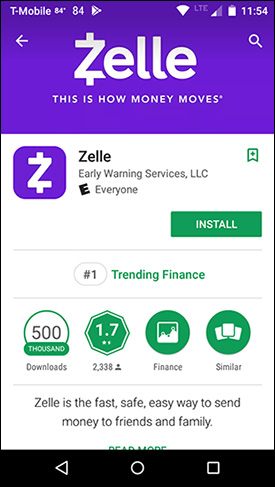

That’s the main issue that P2P has been struggling with at its core: It’s not that no one can get the technology right – many companies already have. It’s that nobody can accumulate the critical mass of users needed to make the system work smoothly. In fact, nobody even really knows what that crucial adoption threshold is. Seemingly every day, a new study shows off impressive adoption statistics that make it seem like reaching that level is just around the corner, but just like tomorrow, it remains always a day away.

What participation rate would we need in order to have a viable P2P system, anyway? When you do the math, it actually goes a long way toward explaining why we don’t have one yet. It’s surprisingly more difficult than you’d think. A LOT more difficult.

Let’s suppose for a moment that a “successful” P2P platform simply allowed two individuals picked at random to exchange money more often than not. Just anything above a 50 percent success rate, that’s all. That would require your app to have an astonishing 71 percent adoption rate in the market – a near-monopoly level of participation by any standard. That’s close to Verizon, AT&T and Sprint’s market share put together. That’s Coke and Pepsi combined.

And that’s just to reach a 50 percent success rate – which, let’s face it, isn’t all that good. If there was a credit card that only worked half the time (and didn’t offer any other special benefits), would you be very interested in it? The standard for mainstream success is a lot higher than half; arguably, it needs to work in 90-95 percent of cases in order to be relied on as a primary means of payment.

It follows that, in order for any two randomly selected entities to have a 75 percent chance of completing a transaction, we’d need just over 86 percent participation. To reach 90 percent, we’d need 94.8 percent of people to be set up for it, and so on. That’s a tall order, to say the least.

In other words, a P2P service wants monopoly-level participation in order to be effective … but many different entities are competing specifically to prevent each other from reaching that goal. The question of which industry segment will be the default provider still hasn’t even been settled. Banks? Phone manufacturers? A payments startup? Mobile carriers? Google? Facebook? Wal-Mart? Any one of those might prove to be the right answer – and at any time, someone else with name recognition and a few billion dollars to spare might decide to throw their own hat in the ring. Each time a new competitor enters the fray, it adds another layer to the fragmentation of the market, and makes it more difficult for any one entity to achieve the necessary dominance that would help P2P actually work the way it’s supposed to.

A Future With Only One P2P App?

Let’s not kid ourselves, though – this state of chaotic equilibrium won’t keep P2P or mobile payments in limbo forever. Eventually, someone will figure it out. What will that look like?

As we’ve explained, functionality isn’t the problem. The technology is already there, and many existing apps work well enough that further innovation is just icing on the cake. It’s all about that critical mass of users, which is another way of saying it’s a compatibility problem.

What’s painfully clear is that the future of mobile payments is not one in which someone might use one of 20 competing apps to send money, and everyone else will use one of those same 20 apps to receive money. Most likely, there will be one or two, and possibly a few minor hangers-on, because that’s all the market will put up with. (How many credit cards do you like to keep on hand, for example? A couple, maybe a few – but much more than that and we reach the point of diminishing returns, and each additional one we pile on becomes more of a complication than a convenience.)

There are two main ways we might get to that point. One would be for a single brand to dominate the industry sufficiently to squeeze everyone else out. Make no mistake, the payoff for the winner would be so lucrative that it’s certainly the first choice for each of the competitors in the arena. On the other hand, it requires a level of dominance that’s almost unprecedented – and the reward for achieving it so great that the competition won’t stop coming.

The other possibility is collaboration – either the top several P2P services agree on a standard that lets them share each other’s customers, or someone else comes up with a common interchange that does an end run around the compatibility issues. This would not be terribly different from the systems that allow other payment methods to work; what’s not clear is whether it would be run by a private company, an industry association, or even a government agency. Examples of each exist in different places within the payments ecosystem.

Why the Winning P2P Standard Won’t Only Be P2P

Finally, it’s worth noting that reaching a critical mass in P2P isn’t going to be only about reaching a critical mass of individual consumers. Inspired by my stepson’s lunch situation, I decided to make a list of the rest of our household’s transactions that weekend, using any payment type. This is the list we came up with:

- Super Donut

- Home Depot

- ARCO

- (the sandwich)

- Amazon

- Duff’s Doggz (excellent Chicago-style hot dogs)

- Rite-Aid

- Steam.com

Did you notice anything about these? Not one of them, other than the sandwich that started it all, was a P2P payment – they were all payments to businesses! In fact, even my stepson’s P2P request had an underlying reason – lunch – that was actually a C2B purchase.

So while P2P is a neat trick, you don’t really send money to your friends very often compared with how many times you buy something from a business. The winning platform will most likely be one that also allows C2B payments, and cheaply.

If there’s one thing credit and debit cards have taught us, it’s that merchants will accept payment methods that carry a fee – grudgingly, if they have already reached a critical mass of acceptance among the public. But there’s no clear winner on either the P2P or C2B side – no MasterCard or Visa that everyone “has” to accept. So, a big advantage in the adoption race will go to whoever can offer C2B payments for free, or at most for a low flat fee.

As we mentioned in our recent white paper, The Reappearing Check, the banks have a huge advantage over non-bank payments companies in that respect, because they have deposit accounts as an underlying goal, while a payments company needs to make money off the transaction itself, or starve. As of now, though, the banks are not ready. On the other hand, neither has anyone else managed to build an insurmountable lead. If there’s one thing we can say for sure about the P2P scene, it’s that it’s still ripe for taking, but the right formula is going to include more than name recognition and more than sending money to your friends. Compatibility is the name of the game – in more ways than one – and a universal standard will need to be there no matter which way you are using it.