In the document world, an “image survivable feature” means exactly what it says: Any mark on a piece of paper that survives the process of being scanned or photographed, meaning it remains legible on the image in digital format. Which kinds of features are “survivable” has changed a lot over the years, as the technology used to copy and capture paper documents has evolved dramatically. Their main purpose, however, has stayed the same. And that purpose is making sure that said documents cannot easily be copied, altered, or faked.

Our UK-based partners at the TALL Group recently published a series of white papers on check security, including this one titled Cheque Clearing System: An Innovative Approach to Defeating Cheque Fraud, which deals specifically with image survivable features (or ISFs) as anti-fraud countermeasures.

Before we get into check fraud, let’s take a look at the evolution of ISFs from simple photocopy “noisemakers” into highly targeted verification tools.

The Early Days: (non-) Image Survivable Features as Copy Protection

Why did they do this? Well, because the easiest way to pirate computer games back then was to copy the disks and give them to your friends, then make a duplicate of the manual for the copy-protection codes. So, the most common technology that the game publishers were going up against in the ’80s was a “dumb” black-and-white photocopy machine that was not designed for color documents, and which had very limited capability to adjust for contrast problems. The black and the dark brown on the Maniac Mansion code sheet were too similar for the machine to tell apart, and the photocopy came out as a blurry mess. The code sheet defeated would-be software pirates by being the reverse of an image survivable feature on the equipment of the time. (In other words, the color scheme rendered the important information NOT survivable.)

The point is, as cameras and scanners get better, and the software behind them gets better, what constitutes an image survivable feature can change – a lot. That’s not to say the same tactics aren’t still in use today; they just have to change with the times as well.

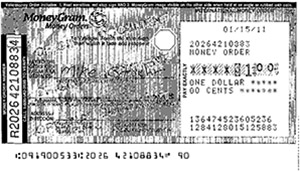

This is not a coincidence: The people who print money orders have a very keen interest in making sure nobody else can create fakes, and so they use printing tools to fool even modern image-capture and duplication devices. This MoneyGram money order has a dark gray background on one side, and a plain white background on the other. This is the reverse of the Maniac Mansion trick: Instead of making the colors so similar that the machine can’t tell them apart, it makes them as different as possible.

That puts the machine in a Catch-22: If it treats the darker side as the “default,” then the light side comes out too faint to be readable when converted to a bi-tonal black-and-white image. If it treats the lighter side as the default, then the dark side comes out unreadable, as in the example at right. This makes an entire side of the document into a (non-) image survivable feature by forcing the machine to choose between preserving one or the other.

That puts the machine in a Catch-22: If it treats the darker side as the “default,” then the light side comes out too faint to be readable when converted to a bi-tonal black-and-white image. If it treats the lighter side as the default, then the dark side comes out unreadable, as in the example at right. This makes an entire side of the document into a (non-) image survivable feature by forcing the machine to choose between preserving one or the other.

Of course, this trick relies on the assumption that the scanner will treat the entire document as a single unit, and that it will apply one-size-fits-all contrast and brightness settings to the whole image. In the case of checks and money orders, it works well, because images of checks and money orders MUST contain only two shades of pixels — either 100% black or 100% white — in order to be legally compliant for the banking system. The process for creating these so-called “bitonal” images involves discarding the color information and setting a brightness threshold, above which all pixels are converted to plain white, and below which all are converted to plain black. It is because of this “thresholding” requirement that money orders are hard to convert into legible images for clearing.

But, as we said, image-capture technology is constantly evolving, and so check scanner technology has found a way to overcome this obstacle as well. By using software to automatically divide the money order into separate areas, the scanner can use multiple separate contrast and brightness thresholds, and come out with an image where all parts are legible. It can even anticipate which kind of money order it is ahead of time, by reading the numbers in magnetic ink printed at the bottom. Score one for the scanner guys!

A similar trick was at work on checks printed with “VOID” pantographs in the background, which would show up big and bold if the document was copied. (This type of copy protection had its heyday around the 1990s and early 2000s, but can still be found sometimes even today.) By taking advantage of the limitations of camera resolution and contrast definition, it was once again possible to thwart forgeries on the most common equipment of the time.

Present Day: Image Survivable Features as Security Measures

Put another way: Instead of a design whose presence is a negative verification test — interfering with the finished image, or marking it as fraudulent — image survivable features are part of a positive confirmation process; if they are not present and/or not correct, then something is wrong.

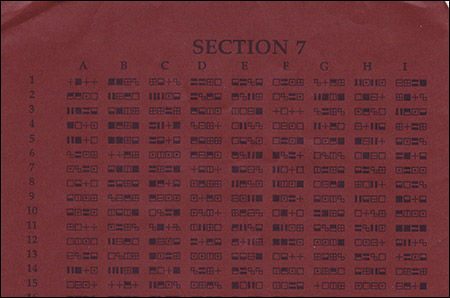

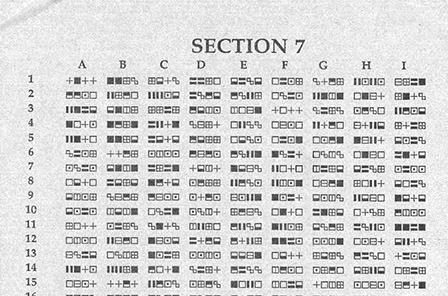

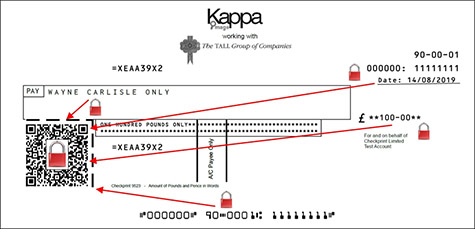

For example, most standard checks in the UK have adopted a Unique Coded Number, or UCN, which is simply a series of letters and numbers that uses a cipher to display important information like the account number, routing number, and check number in scrambled format. When the item is scanned, a computer on the other end unscrambles the code and cross-references it against the MICR line.

Taking it one step further, our partners at the TALL Group have helped develop a new feature called UCNPlus†, which takes the same information and encrypts it into a 2D bar code, as in the sample immediately above. This is the polar opposite of the way copy protection used to work. Rather than simply making the original difficult to physically reproduce, this digital anti-fraud measure uses a feature that can be read by machine — and only by machine. This is like saying, “You can make as many copies of this check as you want, and alter it however you want – but if you don’t know how to fake the code, we’ll catch you anyway.”

This may seem like a subtle change, but it actually represents a diametrical shift in the way of thinking about the role of the image in fraud prevention. Rather than trying to outsmart the camera (or image sensor) and produce an unusable image, security experts that use image survivable features are embracing it as an ally in their mission.

In order to validate the information on the check against the data in the barcode, the security program needs a perfect copy of the original — and that goes both for the bar code and for the other information printed in plain text. After that, the magnetic ink character recognition (MICR) and optical character recognition (OCR) need to be flawless to ensure an accurate comparison. Instead of an enemy to be defeated in the war on fraud, the scanning equipment and image software have become some of the most potent tools on the good guys’ side.

A Black-and-White Question: Image Survivable Features in Check Clearing

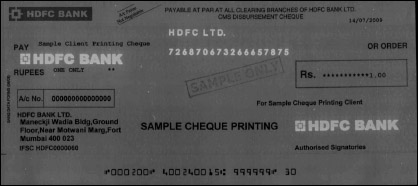

When it comes to “image survivability,” check clearing has one very important difference from everything else. Almost everywhere in the world, the initial high-resolution grayscale image is discarded and converted into a black-and-white image, and THAT is what changes hands between banks in order to complete the transaction. These low-quality images, about 10 KB to 20 KB in size, are referred to as “bi-tonal” because they are exactly that: Each pixel is either completely black or completely white, much like binary code.

In some countries, the bank that scans the check is required to hold on to the original grayscale image for a period of time; in others, it’s discarded almost immediately — but in almost every case, the barebones bi-tonal image is what changes hands, and the grayscale never enters the clearing system. As a result, either a) image survivable features must survive not only the capture process, but also the conversion to pure black-and-white; or b) the anti-fraud testing must be performed by the bank that scanned the check (preferably both of these).

We’ll help you read between the lines here: If you are a bank, this means that you can print whatever security features you want on your own checks — but there is no guarantee the other bank will be looking for them when it scans the check, and even less guarantee that you’ll get those features back in the final image scanned by someone else. Or in other words, if everyone is not using the same standard nationwide, you are on your own. This is why image survivable features on checks need to be designed to be both plain (so they will make it through even the worst image capture and conversion processes) and complex (so that they cannot easily be forged or copied). It’s not an easy job, to say the least!

The Best of Both Worlds

In many countries, checks are printed with a second layer of special ink that’s only visible under ultraviolet (UV) light. This type of protection gives the anti-fraud crowd the best of both worlds: It’s easily readable by both humans and machines — but if you don’t have the right equipment, you won’t even be able to make an accurate copy (or forgery) of it at all.

There are several kinds of widely used UV features, ranging from simple yes/no tests — e.g., whether there is UV printing present on the document at all — all the way up to hidden numerical sequences or the same types of 2D barcodes used in visible ink in the previous example. (If you are interested in learning more about the various kinds of UV security practices, our white paper on the subject is available for free download here. It’s from 2013, but most of the same techniques still apply!)

Because it’s hidden from regular cameras, UV printing can turn what would otherwise be standard information into clever security tests — in the example above, the serial number printed across the center of the check could easily be duplicated if it was printed with regular black ink. Because it’s in UV, though, most criminals wouldn’t even know it was there, and those who did would still have a difficult time reproducing it accurately with readily available technology. Similarly to the Maniac Mansion instructions, the physical printing itself is enough to weed out the casual thief; and the image survivable serial number can then be OCRed and checked against a database for the next level of security.

In other words, when the UV security feature survives the image-capture process, it indicates the authenticity of the document; if it does not, or if it is not present at all, then it has been altered or forged.

While this is by no means a comprehensive list of ISFs, or of the ways in which they can be used, you hopefully now possess a better understanding of their role in document security. With the technology of the past, simply thwarting the camera with difficult backgrounds was often enough to do the job. Today, though, quality optics and image software are both inexpensive and readily available — so you want them working on your side, not the bad guys’.

† UCNPlus is a registered trademark in the United Kingdom by the TALL Group of Companies.