When we see the name Digital Check, most of us naturally associate it with one thing: the desktop check scanner, which has been our main product for two decades. But you’ll also see our company name alongside slogans like “More than 60 Years in Business” or “Since 1959.”

To the astute observer, that presents a bit of a puzzle, since check scanners as we know them didn’t really exist before the 1990s or become popular until after the turn of the millennium. Clearly, we haven’t been making check scanners since 1959 – so what came before that?

The Digital Check story didn’t begin with checks, or with anything digital for that matter, but rather at about the most analog place possible. It was in 1957 that our founder, Thomas Anderson Sr., attended a convention for the U.S. paper industry and got the idea that kicked off our decades-long journey.

At that time, Anderson was working as a paper broker – a job title that would be unusual today, but which served an important function back in the 1950s. For those not familiar with how the industry worked back then, the mills that made the raw paper and the paper-goods manufacturers that made finished products were typically not part of the same company. A mill would produce bulk paper in giant rolls that measured 10 or 12 feet wide and weighed thousands of pounds, and the brokers were the market-makers who were responsible for matching potential buyers with mills that had the amount and type of paper they needed. (Similar jobs exist today, but thanks to automation and long-term forecasting, most of the bustle and excitement of ad-hoc trading is long gone.)

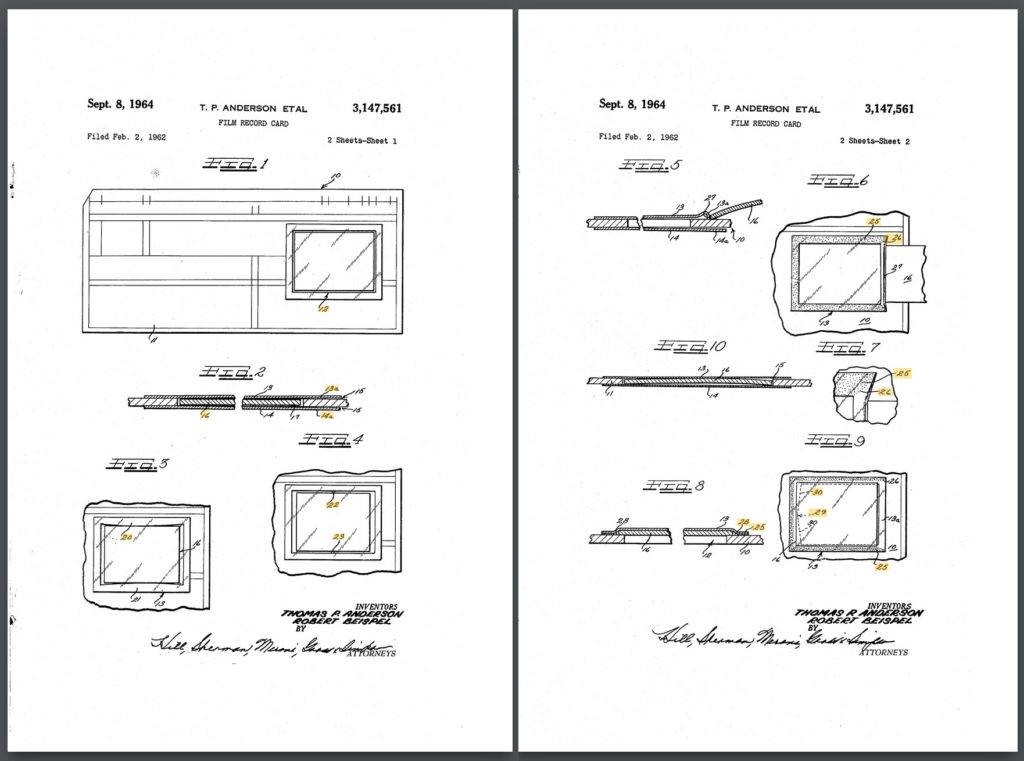

One evening while Anderson was having drinks with his fellow brokers after the conference closing time, one of his competitors opened his briefcase to show off a new invention that 3M had begun making out of the paper from one of the mills he represented. The product was a special card with a square hole on one side for holding a piece of microfilm, and the other side was reserved for computer punch codes that contained information about what was on the film. It was one of the earliest examples of a computerized storage and archive system for important documents, the rival broker boasted, and 3M had named it the “aperture card.”

When it was his turn to take a closer look, the first thing Anderson noticed about the aperture card was that it was just a plain card that left the film exposed on both sides. Why wasn’t there anything protecting it? The answer was just that no one had thought of it, the other rep admitted.

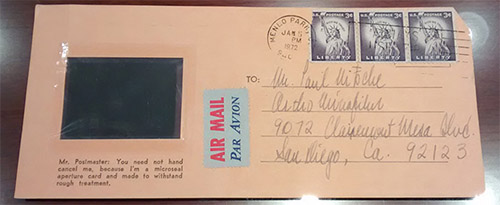

According to family tradition, Anderson then asked one of the other brokers to hand him a pack of cigarettes. But instead of pulling one out to smoke, he took off the plastic wrapper that went around the pack and fashioned a makeshift covering for the microfilm. That idea became the basis for the “suspension-style” aperture card, the main product of the new company that he founded in 1959. The new suspension-style card used a microdot of adhesive to seal the film in place, and so the company had its original name, Microseal.

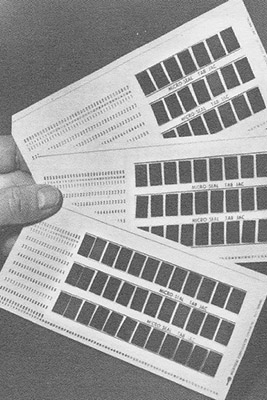

Our journey into microfilm didn’t end there, though. The original generation of aperture cards was designed to hold very specifically sized microfilm “chips” that contained complex, high-value documents like blueprints and engineering drawings. Microseal quickly branched out into cards of all shapes and sizes – most notably for the 16-millimeter film used in those days to copy ordinary documents – and with easy-access slots for as many as 36 negatives that could be easily inserted or replaced. Those cards and “microfilm jackets” were mass-produced in the millions and sold all over the world through an extensive distributor network. Another Anderson-founded company, Photofile, began making similar cards for preserving 35-millimeter film negatives around this time.

Subsequent years would see Microseal adapt to other evolving trends in the industry, such as developing cards for use with line-feed computer printers instead of punch codes, and even a photoreactive “diazo card” that competed with 3M’s similar technology for copying the contents of the film onto a new card without opening the original.

As it turned out, Microseal even outlived its founder, Tom Sr., who passed away in 1990. Our original microfilm business lasted until 1994 under the ownership of Tom Anderson Jr., who sold the Microseal name and the microfilm imaging division of the business to Bell & Howell after a 45-year run. He held onto all the contracts he had with a check scanning company out of Italy and renamed the remaining part of the business the Anderson Imaging Group (AIG).

A year later in 1995, he sold the Anderson Imaging Group and another piece of the document scanning business and officially formed Digital Check Corp. – a story we will cover in a future issue.