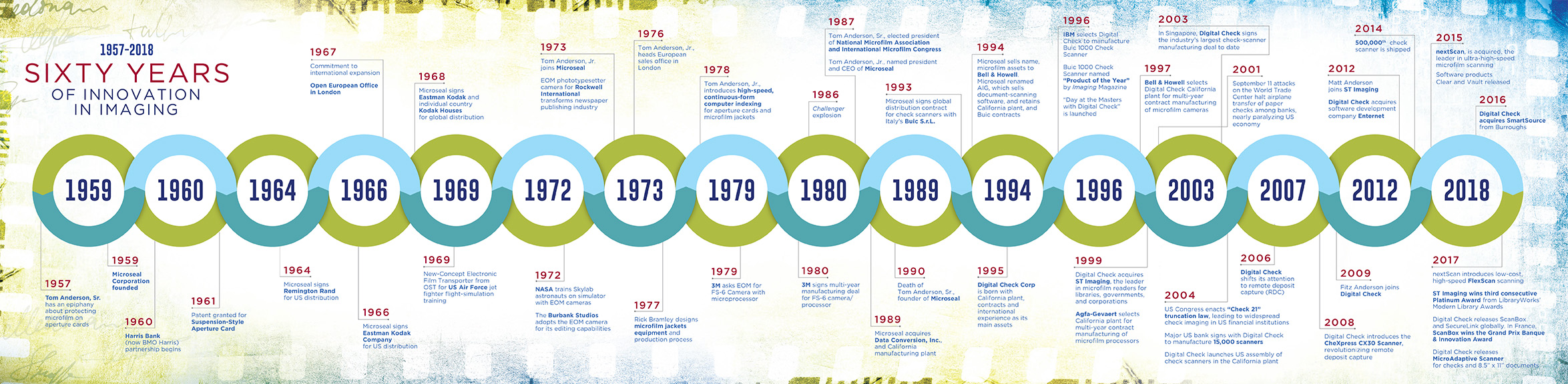

1957: Tom Anderson's Big Idea

A New Way to Protect Microfilm

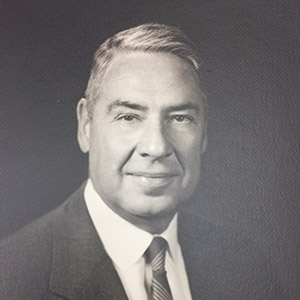

In the mid-1950s, our company founder, Thomas Anderson, Sr., was working as a paper broker – an agent who matched buyers of paper goods to the mills that produced them in bulk. At an industry convention in New York, Anderson and some fellow brokers were hanging out after hours at the Waldorf Astoria’s famed Bull and Bear Bar.

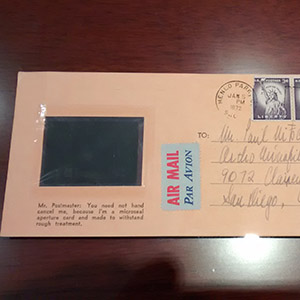

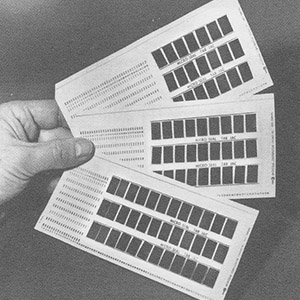

One of the other brokers showed off a new product he was selling – an elongated punch card with a rectangular hole cut in one side. The hole was sized to allow a piece of microfilm to be mounted to it, and a light shined through to read it. The rest of the card contained the information used to sort and file the cards in the vast paper archives used by companies of the time. This unassuming product was known as the microfilm aperture card.

Anderson noticed that the new design, while novel, had one major problem: The microfilm was left exposed on both sides, and easily damaged. As legend has it, he borrowed a pack of Lucky Strike cigarettes from one of the other brokers at the table, pulled off the cellophane wrapper, and used it to fashion a crude protective covering that was transparent enough to see the film through. Little did he know, he had just come up with a new invention that would sell in the millions.